This post is the second in a three-part blog series about research conducted into last-mile and reverse logistics by GSCI Fellow Alan Amling and co-faculty director Tom Goldsby. Read the first post, “The Big Shift in E-Commerce Logistics.”

Fill out the form below to download the white paper.

Our first post introduced The Big Shift e-commerce logistics. In this post, we explore the fulfillment and delivery models uncovered during our research for the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Advanced Supply Chain Collaborative (ASCC).

The last-mile pathway to the customer starts with determining the appropriate fulfillment model to serve the market. Critical in this determination is the reach and service intensity with which the direct-to-consumer (D2C) vendor expects to serve customers.

The right fulfillment network is determined by two factors: reach and intensity.

Reach refers to the geographic coverage of the service area. Two questions are key: Is the vendor seeking to provide one level of service to customers in large metropolitan areas and lower levels of service to customers outside these areas? Or will they provide a consistent level of service across the entire market?

This issue became particularly pronounced after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Previously, online shoppers were concentrated in cities and suburbs. However, the pandemic significantly increased interest among consumers who live well beyond cities to entertain online channels to meet their needs. Vendors, in turn, became more concerned with providing competitive levels of service to those who were beyond their typical reach.

Beyond reach is the intensity with which vendors expect to serve the market. Intensity concerns the assortment of products available and the speed of service (high intensity suggests more extensive product assortments and faster service).

Whereas nationwide coverage in two to five days can be accomplished from one or few locations, getting under two days (sub-2) requires more intense coverage and many more locations. Given the prospects of fulfilling online orders from store inventories, legacy retailers enjoy some advantages. However, with more locations come higher costs. Each location calls for real estate, staffing, and its own allocation of inventory. Strong customer service requires more sites and inventories that are diverse in assortment and ample in quantity to serve the customers in the region at a consistently high level. Yet, more sites should help to lower last-mile delivery costs.

Amazon has pushed the envelope by simultaneously pursuing greater reach and intensity across the markets it serves. The unprecedented build-out of the Amazon distribution network, primarily between 2016–2022, has shifted conventional service standards from two to five days across the entirety of the U.S. market to two days for those who subscribe to the enormously popular Prime membership service. In metropolitan areas with one or more fulfillment centers and delivery stations nearby, service is next-day or sooner. This race to provide higher levels of intensity with broader reach has forced rivals to seek similar levels of coverage.

The correct fulfillment model is one part “what you want to be” and two parts “what your customer needs you to be.”

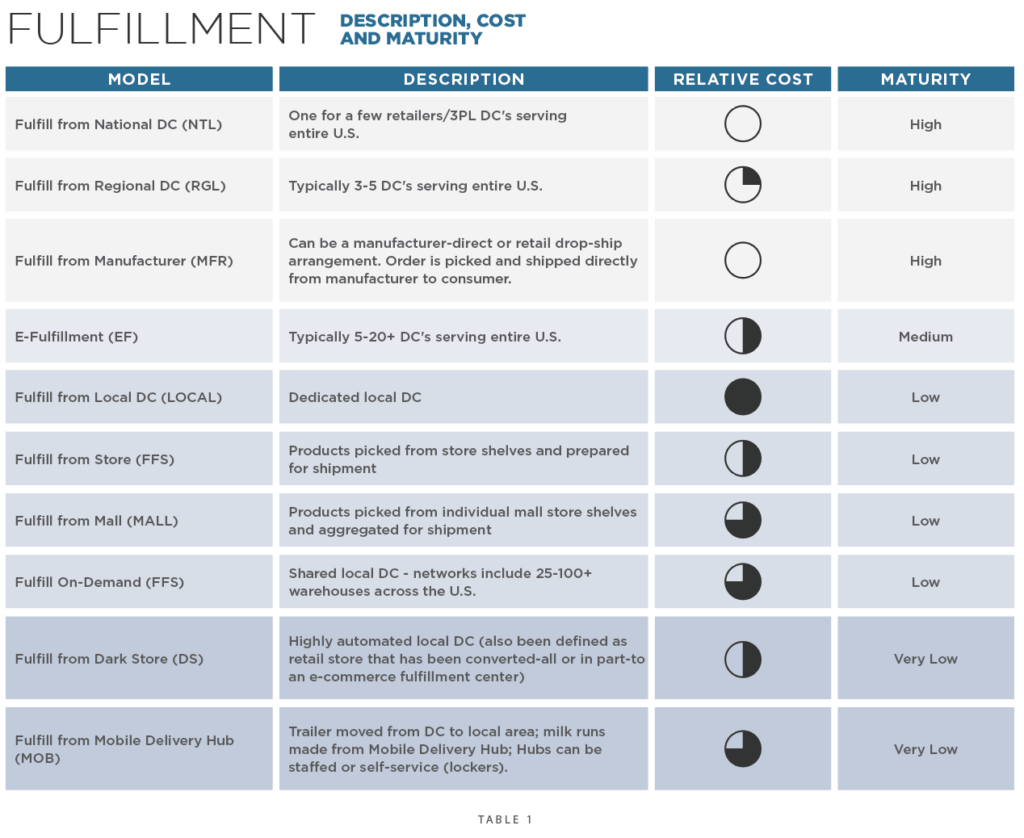

In Table 1, we illustrate the models companies employ to position inventory to meet the needs of today’s consumer. Each model is described in modest detail and accompanied by an assessment of its relative cost and maturity level. Note that relative cost reflects fixed and operating expenses associated with setting up such an arrangement. For example, while a sizeable national distribution center (DC) equipped with an array of modern materials handling equipment is expensive, it’s less costly than regional and local distribution models with multiple facilities and duplicate inventory. The tradeoff, of course, is higher transportation expense and longer lead times.

Of course, fulfillment models do not operate in isolation from delivery and returns models. We must recognize the interplay that takes place to arrive at a determined pathway for the consumer. The right path is the one that positions the right assortment of inventory in the right quantities in locations that allow last-mile transportation with sufficient time to meet specific customer service commitments. Remember that fulfillment may represent the lion’s share of total delivered cost, which is true with intense distribution strategies, such as local DCs, on-demand warehouses, and mobile delivery hubs. In some cases, consumers themselves perform last-mile deliveries with in-store, curbside, or locker pickup. Consider the customer service and total cost implications of bundling fulfillment and delivery options. Not all combinations will prove compatible.

E-Commerce Delivery: The Last Mile Can Be the Longest

On Nov. 10, 2008, DHL Express announced that, after six years of enormous losses, it would withdraw from the domestic U.S. parcel market. The result might have significantly differed if the company had postponed its U.S. entry by a decade.

DHL had tried to compete with UPS and FedEx on their terms. The company invested heavily to build up similar operations and attract volume quickly to achieve economies of scale. However, the incumbents’ package density (i.e., stops per mile and packages per stop) was an insurmountable cost advantage.

Fast forward to 2022. Chances are you’ve seen different branded and unbranded vehicles making deliveries in your area. Incumbent small-parcel carriers are still around. So, what’s different now?

- Local pickup and delivery. This has lowered the entry barrier for dozens of contractors and hundreds of gig workers in every locale across the U.S.

- Expansion of the gig economy. According to Pew Research, 9% of U.S. adults were gig workers in 2021.

- Sophisticated routing software. Previously out of reach for many small businesses, this software is now available as a pay-as-you-go cloud-based phone app.

- Faster delivery times. As Amazon set the bar with its investment in a sub-2-day Prime network, other retailers have been forced to match their offerings. As a result, market delivery time has shifted and is nearing same-day on many occasions.

UPS and the USPS continue to deliver the most parcels in the U.S. However, Amazon already delivers more packages than FedEx and is on its way to becoming the country’s top small-parcel carrier. Regional carriers are trying to capitalize on their gains and push further into coast-to-coast package delivery. East Coast regional carrier LaserShip acquired West Coast carrier OnTrac in 2021 for $1.3 billion. The merged companies launched a transcontinental delivery service in 2022 and plan to add additional locations in Texas in 2023.

Of all the changes in last-mile delivery, the most significant is the increased investment in logistics infrastructure and networks from retailers. Brick-and-mortar retailers like Target invested millions in inventory control systems to dual-utilize store inventory for delivery and curbside or locker pickup. Couple this with Target’s $550 million investment in Shipt, a same-day gig delivery company, and the retailer couldn’t have been in better shape for the e-commerce acceleration in 2020.

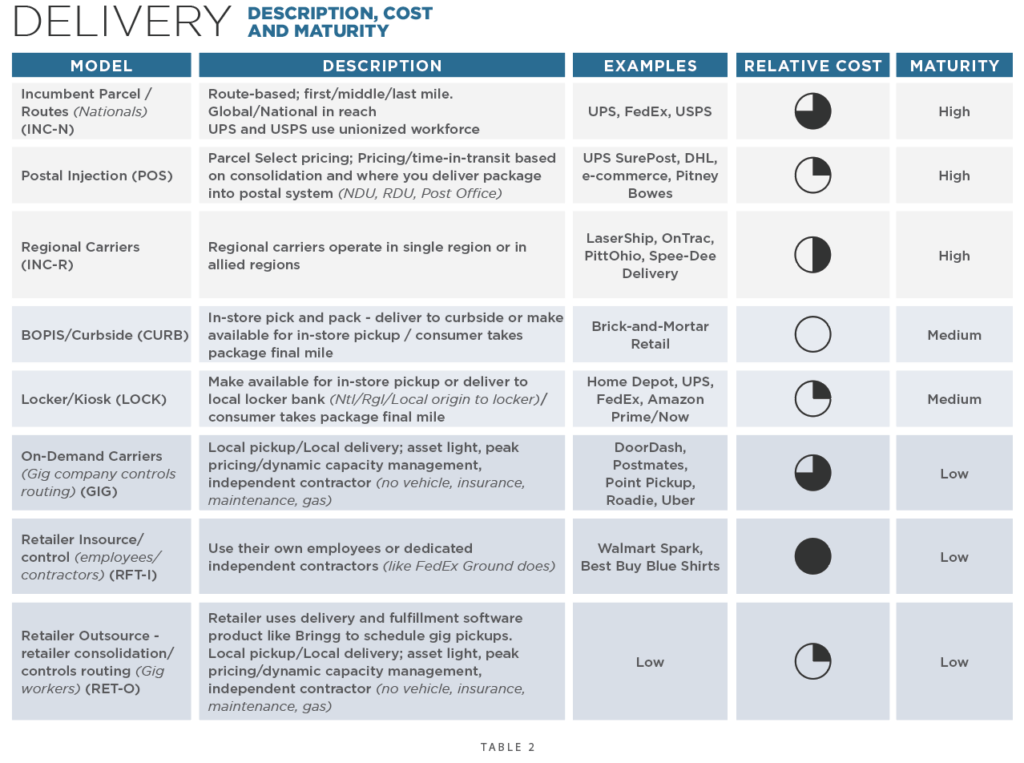

Today, most retailers use a mix of delivery methods to balance customer service, speed, and cost requirements. Table 2 illustrates the eight different last-mile delivery models identified by the ASCC research team. Like fulfillment models, they range from mature, longstanding forms of delivery to those, such as robotic deliveries, that have yet to materialize at scale.

Not all delivery models will work with a given fulfillment model and vice versa. For example, a gig delivery model from a regional distribution center is not viable. Likewise, the incumbent carriers’ route-based networks would not fit with ship-from-store, same-day delivery.

Tailoring the Perfect Last-Mile Delivery Experience

The incumbents have a strong service advantage. But it comes at a cost. These carriers attempted to change their volume distribution to be more B2B—where on-time delivery is a high priority and they can achieve better margins. If a carrier misses a delivery date for a box of Post-it Notes, they aren’t likely to get an angry phone call about it. However, they can count on an angry call if they miss a just-in-time delivery to a manufacturing plant.

These firms are focusing on small-to-mid-size-business (SMB) shippers who don’t have the volume to command more significant discounts. This new focus is exemplified by UPS’s “better, not bigger” strategy. Since mid-2020, this approach has boosted UPS’s profitability considerably in the capacity-constrained shipping environment. For the full-year 2022, UPS grew domestic and international parcel operating profit by 2.2%, even as volume dropped by 3.8%.

Speed advantage belongs to the flexible, on-demand gig and retailer networks. Many retailers followed Amazon’s lead and developed hybrid networks, using independent contractors for high-density route-based deliveries as well as handling same-day and overflow shipments with gig delivery drivers.

E-commerce sales of big and bulky items soared during the pandemic, fueling new home delivery solutions for these larger items. PICKUP, for example, leverages former military members who drive pickup trucks to deliver items such as furniture from Pottery Barn and other retailers. Roadie, a gig delivery company acquired by UPS, does big and bulky deliveries for Home Depot and Tractor Supply.

Outside of customer pickup models, the lowest-cost delivery alternative for low-weight parcels is postal consolidation. In this model, companies pre-sort their volume to regional or local postal facilities for last-mile delivery by the USPS. The time required to consolidate volume can create lead times of over a week, but it continues to appeal to cost-conscious shippers. DHL eCommerce Solutions, Pitney Bowes, UPS Mail Innovations, and others leverage this postal injection model.

Retailers often deploy a mix of delivery methods to optimize their network. Amazon may use its contractor network for Prime one-day delivery, gig network for same-day, and UPS for rural deliveries or those made from a regional distribution center.

In the last blog post in this series, we will uncover the Wild West of e-commerce returns and prepare you for the Next Big Shift in e-commerce logistics.