This is the first post in a new series on Maritime Shipping. With 80% of global cargo moved by ships, this series aims to provide clarity to the challenge of how goods are moved on the high seas and investigate potential alternative global trade routes.

Again and again, global supply chains are being challenged. For those in the maritime industry, this is nothing new. With each shipment, the supply chain faces varying degrees of complexity. But while the pandemic is behind us, multiple geopolitical events have refocused the spotlight on supply chains for both businesses and consumers.

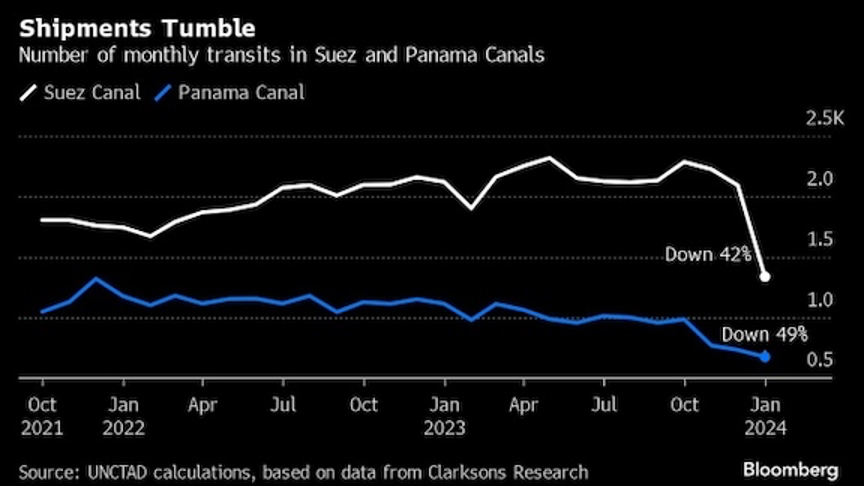

Although much attention has been placed on Houthi attacks in the Red Sea (Suez Canal), other maritime chokepoints are just as critical. In this post, I’ll use a logistics perspective to review the operational costs resulting from the Red Sea crisis.

Although only 12% of global trade sails through the canal, the cost of transportation, the origin and destination, the financial impact on the region—particularly Egypt—and the environmental impact of sailing around the Cape of Good Hope are significant.

Usually, nearly all containerized freight from Asia to Europe and Asia to East Coast ports in the United States sail through the Suez Canal. The current situation impacts all manufacturers in the EU and the US seeking parts as well as consumers. While shipments will arrive at ports, they will be up to 14 days late to Rotterdam and up to 10 days late to New York. We can accept late cargo in a global supply chain by adjusting our logistics plans. But today’s situation in the Red Sea is quite different compared to the pandemic when managers were unsure when or if their cargo would arrive.

Describing the impact on shipping rates by category, Omar Nokta, shipping analyst at Jeffries, stated that “21% of global container shipping moves transit the Suez, with the share at 12% for refined product, 11% for LNG [liquid natural gas], 8% for LPG [liquefied petroleum gas], 8% for crude and 5% for dry bulk. For crude tankers in the Suezmax size category (1-million-barrel capacity) or smaller, the share jumps to 20%.”

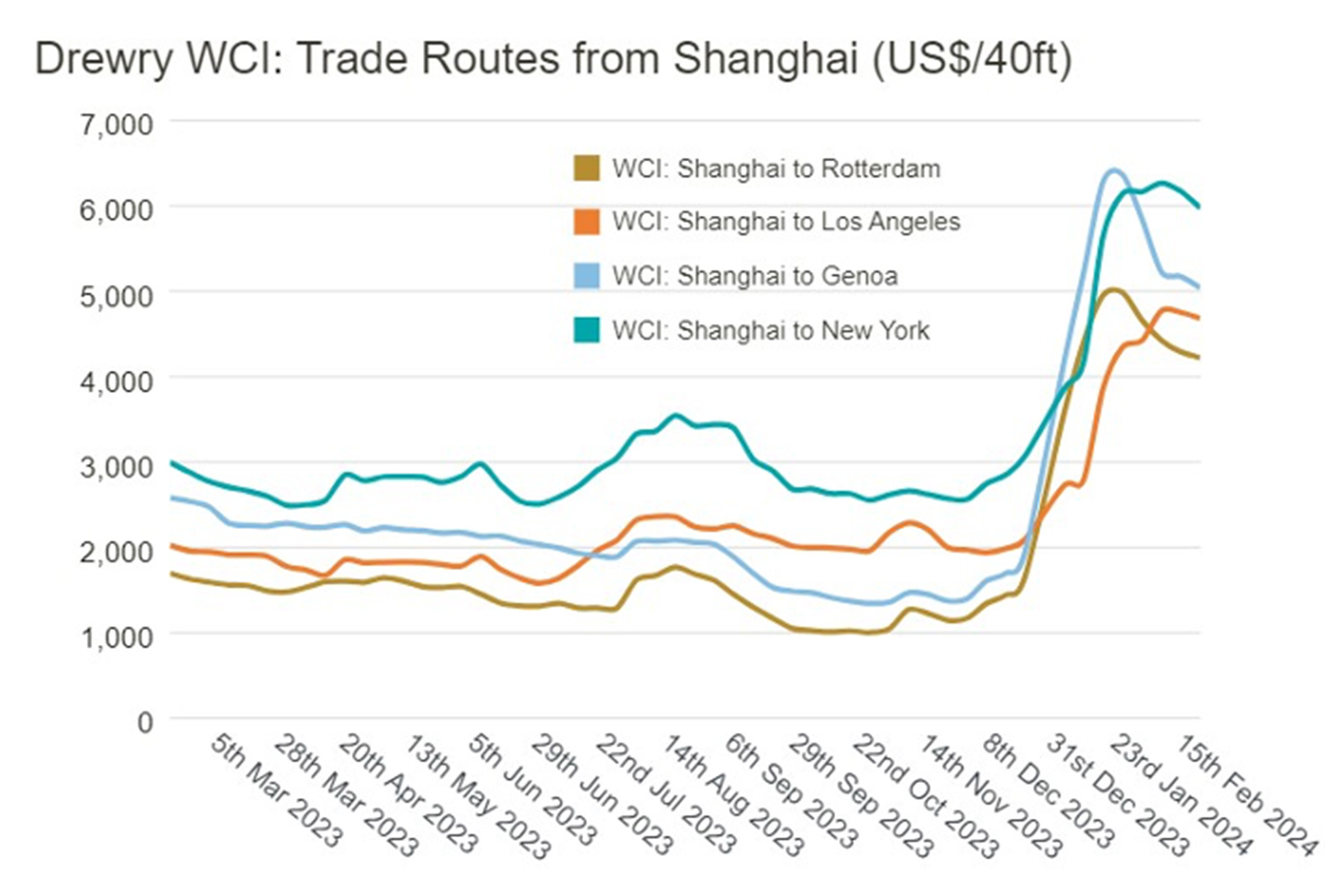

Over the course of a year, between February 2023 and 2024, spot rates for a 40-foot ocean container (FEU) from Shanghai to Rotterdam increased 158% for an average cost of $4,221. However, the spot rate on the same 40-foot container on January 25 reached $4,984 (three months earlier, on October 26, the rate was $1,004). Closer to home, the spot rate on a 40-foot container from Shanghai to New York increased from $2,881 to $5,976 since last February. Yet container rates didn’t just increase on voyages through the Suez Canal. The spot rate from Shanghai to Los Angeles experienced an annual increase of 139%, from $1,959 to $4,683 (the rate was as low as $1,961 in October 2023. Those containers do not navigate anywhere close to the Red Sea.

The impact of the Red Sea situation has a local cost. For Egypt, the lack of vessels utilizing the canal reduced toll revenues by 50%. According to Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, income from the Suez Canal, which used to bring Egypt nearly $10 billion annually, has decreased by 40 to 50 percent.

With increased sailing time around the Cape, vessels are increasing their speed from 16 to 20 knots to maintain some schedule reliability (a factor critical to satisfying customers and consumers). The longer distance traveled increases the amount of fuel consumed. The increase in ship bunker fuel from the increase in miles has been estimated to be an extra $100,000–$250,000 paid at the “pump,” based on vessel size. Since the vessel is at sea longer, the charter rate (similar to renting a car for a day) has also increased by $350,000 one way.

Besides the increased operating costs of avoiding the Red Sea, there is also a financial environmental cost. The 40% increase in miles traveled, plus the increases in vessel speed, has increased greenhouse gas emissions. Robin Meech, managing director of Marine and Energy Consulting Limited, estimates an additional 7 million tons of bunker if the situation continues for one year. UNCTAD estimated this alternate course would increase emissions, sailing from Singapore to Rotterdam, by 70%.

Bear in mind that Singapore is on the southern end of many large Asian container ports and, thereby, closer to Rotterdam and New York. Besides the increase in emissions, a knock-on effect will increase the cost of shipping: the EU-ETS (European Union-Emission Trading System). The ETS assesses a fee based on the amount of emissions discharged from a vessel on the entire voyage, either originating in or destined for a European Union port. A longer journey equates to more emissions, resulting in a higher assessed fee. The fees are assessed on shipments to or from an EU port and will directly impact US consumers since the EU-ETS fee will be assessed, for example, on vessels sailing from Rotterdam to New York and back.

At this point, I’ve discussed operating costs, the cost to the Egyptian economy, and the environmental cost. But others include regular crew costs, as they will be at sea longer, as well as emergency wage costs if the vessel does transit the Red Sea and the crew members accept the voyage (the International Maritime Union allows members to refuse a voyage without penalty and still be paid for loss of wages). Maritime insurance rates will increase for shipowners. The longer this goes on, the more expensive it will be for everyone. So, let’s hope the situation gets resolved soon, though exactly when is anybody’s guess.