This is the final post in a three-part blog series about research conducted into last-mile and reverse logistics by GSCI Fellow Alan Amling and co-faculty director Tom Goldsby. Read the first post, “The Big Shift in E-Commerce Logistics.”

Download the white paper by filling out the form below.

In the first two blog posts of this last-mile series, we unveiled the future of e-commerce delivery. In this post, we focus on the return leg. As businesses evolve their thinking about customer returns from the “cost of doing business” to a competitive imperative, speed becomes a key differentiator. Enabled by new business models and the rise of the retailer logistician, the next shift in e-commerce logistics could be even more consequential than the last.

Returns: The Third and Most Wobbly Leg of the Stool

Collecting returned merchandise from consumers is a critical element of the customer experience. It’s also a challenge for businesses. Unfortunately, much of what gets shipped through e-commerce comes back as product returns. According to the National Retail Federation, 21% of items sold online in 2021 were returned, amounting to $761 billion in value.

Some product segments experience much higher return rates. For apparel and footwear, the number can exceed 30%. Compare that to in-store purchases, which experience 9% returns. On average, it costs $33 (or 66%) of the cost of a $50 item for retailers to process a return.

Why is so much product coming back? Vendors employ liberal returns policies to achieve competitive parity. Hassle-free returns assure that vendors assume the burden for returns and entice consumers to shop unconcerned. Convenient returns are a key component of the online shopping experience for consumers.

Consumer survey results back up these assertions:

- 96% would shop again with a retailer based on a good returns experience

- 84% of online shoppers are more likely to buy from online merchants who offer free returns

- 80% of consumers read the return policy before making a purchase

- 68% of shoppers indicate that free return shipping is key to a positive return experience.

Despite the final data point regarding refund fees, Zara and H&M are testing the issuance of returns fees to temper consumer tendencies to buy more than they intend to keep and to assume some of the financial burden associated with returns. Retail peers, keen to share the burden if they can, will likely observe how consumers react to such fees.

A deeper analysis suggests that returns management involves more than merely collecting items and issuing customer credit. It starts in the presale stage when consumers review the vendor’s return policy. Beyond issuing such a policy, vendors can take preventative measures during this transaction stage to prevent returns—after all, the best return is the one that never happens.

To prevent mistakes and purchase errors from the outset, retailers may direct customers toward products that would better serve them. Apparel retailers offer virtual fitting technology to allow customers to visualize the products before submitting their orders. Customer support can also manage redundant items and the common tendency to bracket by ordering up and down a size.

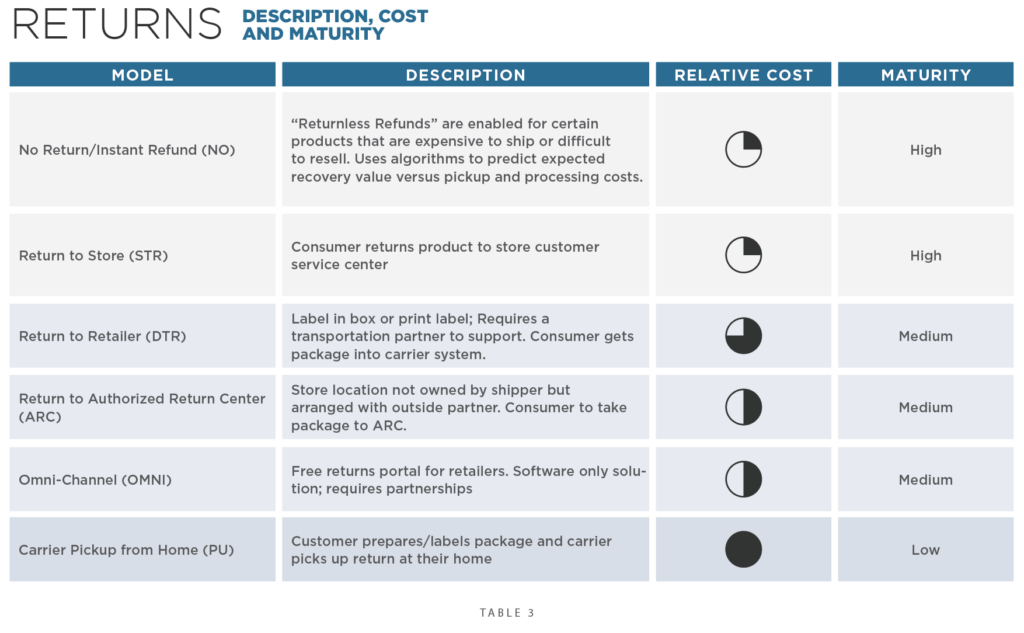

Returns are a six-step process, commencing with initiation. Once the consumer indicates interest in returning an item, approved returns are inducted through a transfer point. The different models for collecting, processing, and dispositioning returns appear in Table 3.

Our analysis suggests that effective returns management is among modern supply chain management’s most overlooked and undermanaged aspects. In an age when consumers reign supreme, vendors feel obligated to provide liberal returns and consider extraordinary expense the cost of doing business. However, few companies have tracked the costs. Further complicating this issue, in most organizations, no one is accountable for returns, and metrics around returns volume, process effectiveness, and costs are not tied to individuals or their compensation. As a result, returns receive little attention, and the problem proliferates unfettered.

There are forces at work, however, that are changing this outlook.

The Economics of Non-Economic Considerations

To this point in our analysis, we have examined the pathways to the consumer, focusing on the operational means and economic costs associated with reaching the market and bringing unwanted products back. Yet these considerations fail to fully capture the growing complexity of serving the market in light of emerging concerns for the broader environmental and societal factors in e-commerce.

A larger number of small-volume shipments presents its own issues, with more vehicles required to accommodate the demand. More vehicles lead to more congestion on roadways and an increased potential for accidents. It also means more miles traveled, resulting in higher costs and elevated levels of carbon emissions. Packaging for delivery of individual items contributes to sustainability issues with e-commerce. While difficult to calculate its carbon footprint compared to brick-and-mortar retail, one analysis shows that a basket size of 5.5 items represents a break-even between the two provisions.

Sensitivity to environmental concerns also serves as a differentiator among vendors. The environment is a primary concern for Gen Z consumers. Some retailers have found that exposing consumers to the realities of the carbon footprint associated with delivering products and processing returns has made shoppers more conscientious of these issues and, in turn, more deliberate in their shopping. The inverse is also possible. Corporate insensitivity to environmental and societal concerns can result in disaffected consumers and draw regulatory scrutiny.

Of course, most non-economic factors yield economic outcomes, too. Ultra-liberal returns policies lead to considerable waste and burden placed on the vendors. Fraud can run rampant in the provision of sales and returns. The National Retail Federation estimates that for every $100 in returned merchandise accepted by retailers, $10.30 is lost due to fraud.

Yet this fraudulent activity is regarded by most retailers as a cost of doing business. Porch piracy is regarded similarly by consumers who fall victim to opportunistic thieves. Additional non-economic concerns include privacy. Vendors look to consumer search and purchase activity as valuable data. At what risk to consumer privacy is this data gathered, shared, or sold?

Create a Winning E-Commerce Logistics Recipe

Cutting-edge research often asks more questions than it answers. So is the case of serving the diabolical consumer through last-mile fulfillment and delivery. Not only are the models for serving consumers innovating and changing rapidly—so are the consumers themselves. Several people ventured into e-commerce only recently, and their interests are still developing and maturing. There are also vast swaths of the country that receive comparably lesser forms of service than the more populated cities and suburbs. They have not yet been granted the opportunity to become diabolical. On the other hand, we have digital natives: younger consumers who demand greater levels of transparency and higher achievement in sustainability.

This all leads to the mass e-commerce market breaking down into distinct segments with different appetites—for different kinds of goods as much as service variants that demonstrate preferences across different dimensions. One subset of consumers seeks a higher share of domestic content or Made in America product labels. Others seek to know where products are produced and in what manner. This way, they can ensure these products are free from forced labor and conflict minerals and do not leave a significant carbon footprint. And still, others seek assortment at competitive prices with high levels of convenience. Those who serve the consumer market can no longer assume it is large and faceless.

Over the course of three blog posts, we have laid out The Big Shift in e-commerce logistics and the variety of fulfillment, delivery, and returns solutions. The enduring truth is: there is not one best supply chain. The different models are your ingredients, now use them to create a winning recipe for your company and customers.