In August 2024, the University of Tennessee Global Supply Chain Institute published the “EPIC Index Update and Country Risk Report,” a white paper by Alan Amling, Alex Rodrigues, and Sara Hsu based on research they conducted into supply chain disruptions for the Advanced Supply Chain Collaborative. Download the white paper.

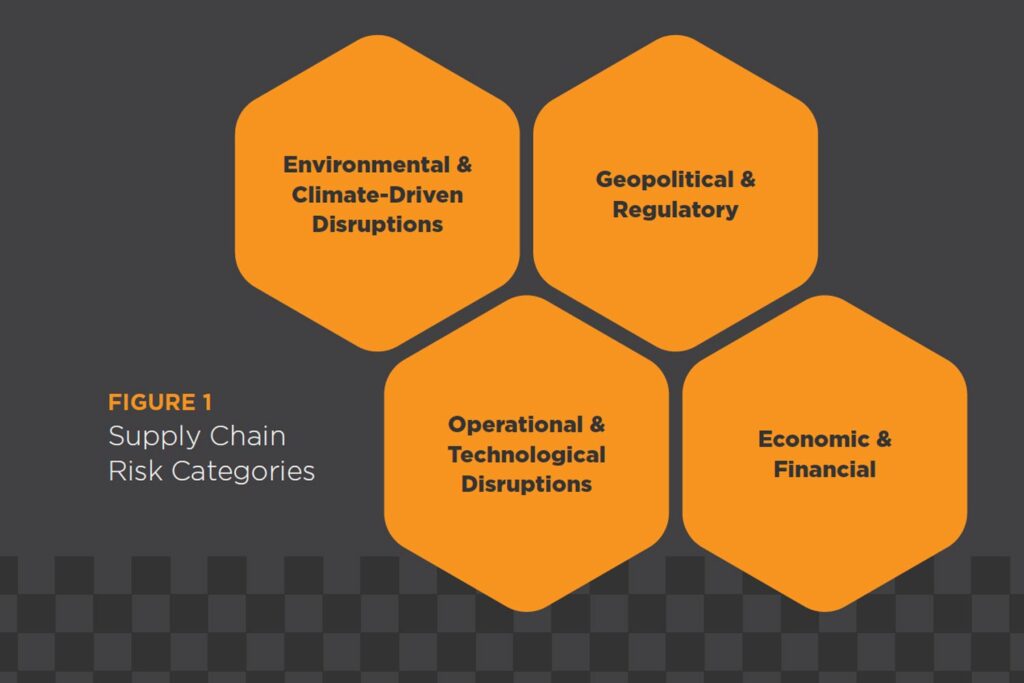

Global supply chains face unprecedented risks, including environmental and climate-driven disruptions, geopolitical and regulatory actions, operational and technological disruptions, and economic and financial challenges. Emerging risks stemming from the rapid advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the threat of a new Cold War also exist.

While supply chain managers have been attuned to potential disruptions for decades, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of managing risks through the end-to-end supply chain. The scale of the pandemic was so grand that it impacted all areas of supply chains across industries and around the globe.

Traditional risk management techniques, which included examining potential disruptions in specific areas, were considered insufficient, as risk appeared everywhere. Supply chain visibility and mapping rose to the forefront as supply chain managers strove to identify secondary sources, operations centers, and logistics resources to ensure a continuous supply of goods and services.

The EPIC Framework

The University of Tennessee Knoxville’s Global Supply Chain Institute strives to provide supply chain professionals with critical information regarding global supply chain risks. The EPIC framework was conceived in 2010 and initially proposed in the 2014 book Global Supply Chains: Evaluating Regions on an EPIC Framework. Global supply chain managers benefit from a tool that helps them assess their supply chain location decisions, identifying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the different regions in the world.

The EPIC framework provides the structure for assessing supply chain readiness in regions around the globe from economic, political, infrastructural, and competence perspectives. The framework defines and explains these dimensions to assess their potential impacts on the effectiveness of global supply chain management activities. It measures and evaluates the levels of maturity a country and geographic region holds, specifically regarding its ability to support supply chain activities. Each EPIC dimension is assessed using quantitative scores based on data obtained primarily from publicly available databases from The World Bank (e.g., World Development Indicators, Worldwide Governance Indicators, and Logistics Performance Index). Additional metrics were obtained from other publicly available sources such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), International Union of Railways (UIC), Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), CEIC Data Company (CEIC), International Energy Agency (IEA), and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

The four dimensions of the EPIC framework capture the essential characteristics critical to managing efficient and effective supply chains.

ECONOMY [E]

- The Economy dimension assesses the country’s economic output, potential for future growth, ability to attract foreign direct investment, and ability to generate a steady return on investments made in the country.

- The variables used to assess the Economy dimension are Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and its growth rate, population numbers, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), exchange rate stability, consumer price inflation, and trade balance.

- These variables represent the potential opportunity for organizations wishing to engage in supply chain activity in the country.

POLITICS [P]

- The Politics dimension assesses the political landscape and how well it nurtures supply chain activity.

- The variables considered in the Politics dimension include ease of doing business, bureaucracy and corruption, legal and regulatory framework, tariff barriers, risk of political instability, and intellectual property rights.

- These variables influence the environment in which supply chains operate.

INFRASTRUCTURE [I]

- The Infrastructure dimension tracks variables that strongly influence how physical supply chain structures and facilities required for operations are managed. It represents the potential for leveraging these activities.

- The variables considered in the Infrastructure dimension can be broadly classified into physical, energy, and telecommunication structures.

- The physical infrastructure covers roadways, the railway network, and water and air transportation activity. The energy infrastructure is responsible for the supply of electricity and fuel. The telecommunications infrastructure is captured by the extent of telephonic and internet-based structure and activity.

- Infrastructure enables trade, powers businesses, connects workers to their jobs, creates opportunities for struggling communities, and protects countries from an increasingly unpredictable natural environment. It directly impacts the economy as a whole, especially supply chain performance.

COMPETENCE [C]

- The Competence dimension assesses the general supply chain skill levels of both the workforce and the logistics industry in countries that can form part of an organization’s supply chain.

- The variables included in the Competence dimension are labor productivity, labor relations, availability of skilled labor, education level of line staff and management, availability and competence of the existing logistics service industry, and the speed at which customs and security clearances occur.

- The sophistication of supply chain support available through the country’s logistics industry affects the ability to operate high-performing supply chains.

The increasing number of risks and the rise of uncertainty in supply chains are daunting. Rather than considering each risk that can impact particular functions, leaders may analyze the potential for removing one or more supply chain nodes. Looking at the supply chain in this way can simplify the risk management process and assist managers in wargaming the impact of disruptions. Managers can seek alternative suppliers, operations and logistics providers, or capabilities to manage unforeseen outages.

Download our free paper to learn about all of the indicators in each dimension and the ranking of countries in the EPIC Index. Beyond the data, we provide supply chain managers with a summary of supply chain risks for every world region. We also discuss the primary global risks in four major categories: geopolitical and regulatory, economic and financial, environmental and climate-driven, and operational and technical.

Is your company interested in partnering with us to explore advanced concepts in supply chain management? If so, visit ASCC.

Download the white paper using the form below to read more about developing the next generation of supply chain planning talent.